Have you ever ordered a meal at a restaurant and thought, “Wow, this could feed two people!” You’re not imagining it.

Over the last few decades, our portion sizes have quietly ballooned. This trend of oversized meals didn’t happen by accident or because Americans deliberately asked for bigger portions, it’s rooted in restaurant economics. The actual food on your plate is one of the cheapest parts of running a restaurant. It’s all the operating costs that are expensive: rent, staff wages, utilities, marketing. So to make you feel like you’re “getting your money’s worth,” many restaurants increase portion size.

A plate heaped with pasta or fries is cheaper than paying another server, and it looks generous, satisfying, and worth the price. We’ve have been trained to equate more food with more value. The result is that we have been subtly trained to expect portions that are 2–3 times larger than what our beautiful Goddess bodies actually need.

So, what can we do? It’s not more willpower, it’s about outsmarting your environment and honoring your body as the divine vessel it is.

Trick your Brain on Portions

Research shows that the more food we’re served, the more we eat. This is called the portion size effect, and it’s one of the most consistent findings in nutrition psychology. Usually we don’t even realize it, particularly if we are distracted, tired, or have lost the connection to our hunger/satiety cues.

Even if we’re full, we tend to finish what’s on the plate. Especially when restaurant portions have become our mental baseline for what “normal” looks like. And let’s not forget the generational imprint many of us carry: being taught not to waste food and to “clean your plate” (left over from when food was scarce).

But a Goddess doesn’t measure her worth in empty plates!

Research from Cornell University shows that people consistently eat more when they’re given larger plates or bowls, simply because it looks like less food. In contrast, using a smaller plate tricks your brain into feeling satisfied with a modest portion. It creates a sense of abundance with less food.

What to do:

- Use a salad plate instead of a dinner plate

- Serve single portions and portion servings into a dish instead of eating from bags or large containers

- Trust that you can always go back for more if you’re still hungry

- When dining out, assume your portion is for two. Cut your food in half or ask for a to-go box as soon as your meal arrives and pack it up before you start eating (out of sight, out of mind)

- You could instead share a dish with a friend or order from the appetizer menu

Eat Slower

One of the most powerful things you can do? Slow Down.

Would a Goddess wolf down a sandwich while scrolling her inbox? No. She’d create space to taste, breathe, receive. She would make eating a ritual and a space to treat herself as the precious being that she is.

When we eat quickly, we miss the signals that tell us to stop. This includes time time for insulin to respond and for signals of fullness to reach the brain. By eating slowly, glucose is released more slowly into the bloodstream reducing blood sugar spikes. Slowing down also gives your brain the time it needs to get hormonal signals that tell it you’ve had enough (before you’ve eaten too much!).

A 2020 study in Nutrients found that eating slowly significantly reduced post-meal blood sugar spikes and glycemic variability, even in healthy individuals. Another study in people with type 2 diabetes showed that slower eating increased feelings of fullness and reduced hunger, even if hormone levels (like GLP-1) didn’t change.

In fact, a meta‑analysis showed that individuals who eat at a faster pace have significantly higher odds of developing metabolic syndrome (a cluster of risk factors including elevated fasting glucose, abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension). By contrast, eating slowly is associated with lower BMI and reduced cardiometabolic risk.

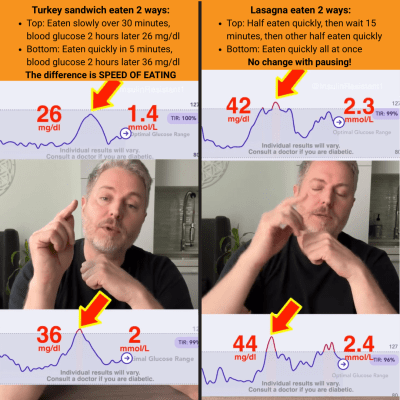

A powerful demonstration of this comes from Justin Richard’s Insulinresistant1 account on Instagram. He compared eating a turkey sandwich in 5 minutes vs 30 minutes and showed blood glucose levels differed by 10 mg/dl! That’s significant!

In another experiment, he ate half his lasagna quickly then waited 15 minutes and ate the other half quickly. This experiment showed no change in blood sugar levels, so it REALLY is about the speed you are eating.

What to do:

- Your brain needs about 20 minutes to register fullness, so eat slowly… like a Goddess!

- Set your fork down between bites and chew each bite thoroughly

- Eat without your phone or TV to notice your body’s cues

- Pause frequently through you meal and ask yourself: Am I still hungry? Notice how your stomach feels, if you’re feeling 70–80% full that’s usually enough. Your fullness is likely catching up with you. And if it’s not, you can always eat again soon!

It’s not your metabolism that’s broken, it’s the system. We’ve been buried under oversized portions, fast eating, and food marketing for too long. It’s time to get back to honoring our bodies and treating ourselves like the Goddess’s we are. Would a Goddess inhale her food over the sink? Or would she prepare a well-proportioned meal of fresh foods and eat it on the good dishes?!

Start small: Slow your pace. Use a smaller plate. Pause between bites. These shifts sound simple, but they’re incredibly powerful when practiced consistently. Instead of just fuel, eating becomes an act of devotion, and a chance to feel honored, nourished and deliciously satisfied.

Want to book a complimentary call w Juniper to discuss your struggles and goals? Click here

References

- Nishimura, R, et al. Effect of Eating Speed on Glycemic Control. Nutrients, 2020; 12(10), 3106.

- Angelopoulos, TJ, et al. Eating Slowly Increases Satiety in Overweight and Obese People With Type 2 Diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care, 2014; 2(1).

- Angelopoulos T, Kokkinos A, Liaskos C, et al. The effect of slow spaced eating on hunger and satiety in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2014 Jul 2;2(1):e000013.

- Saito Y, Kajiyama S, Nitta A, et al. Eating Fast Has a Significant Impact on Glycemic Excursion in Healthy Women: Randomized Controlled Cross-Over Trial. Nutrients. 2020 Sep 10;12(9):2767.

- Yuan SQ, Liu YM, Liang W, et al. Association Between Eating Speed and Metabolic Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Nutr. 2021 Oct 20;8:700936.

- Wansink, B., & van Ittersum, K. The Visual Illusions of Food: How Large Plates and Packages Can Undermine Healthy Eating. The FASEB Journal, 2006; 20(4), A618.

- Robinson E, McFarland-Lesser I, Patel Z, Jones A. Downsizing food: a systematic review and meta-analysis examining the effect of reducing served food portion sizes on daily energy intake and body weight. Br J Nutr. 2023 Mar 14;129(5):888-903.

- Higgins K, Hudson J, Mattes R, et al. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Effect of Portion Size and Ingestive Frequency on Energy Intake and Body Weight Among Adults in Randomized Controlled Trials. Curr Dev Nutr. 2019 Oct 24;3(Suppl 1): nzz044.P08-007-19.