Protein is one of the main building blocks of the body. It is composed of amino acids, which are used by the body for structure (like muscle), storage, transport, enzymes, hormones, immune antibodies, neurotransmitters, and more. These factors are what makes things happen in the body at both cellular and larger levels. Dietary protein helps us feel better, maintain muscle, and feel satisfied. People with higher protein diets even have lower risk of metabolic syndrome,1 a group of conditions related to cardiovascular disease including high blood pressure, high blood sugar, excess body fat around the waist, and higher levels of cholesterol or triglycerides.

Despite how important this essential nutrient is, we are eating less than ever. Food manufacturers entire us to eat more processed foods and our foods are lower in protein due to changes in the growth conditions. Estimates suggest the Paleolithic diet was 37% protein, compared to just 16% in modern diets.2

Protein helps preserve muscle. Research shows that this becomes even more important as we age.3 Older study subjects required twenty grams of whey protein (providing two grams of the amino acid leucine) to stimulate muscle protein synthesis.4 This was twice the amount needed compared to younger subjects.

Maintaining muscle is also important for people on weight loss diets. When people lose weight, the loss is a combination of fat and muscle. Higher protein diets show similar overall weight loss, but better muscle maintenance and fat loss.5 After four months of a diet comparison study, subjects on a higher protein diet lost 22% more fat compared to subjects on the lower level.6 The higher protein group also had more subjects complete the study, suggesting that they were more satisfied.

Protein also slows down the speed at which the meal passes through the stomach, helping us feel more full.7 Overweight children on a weight loss diet showed lower levels of hunger throughout the day when given a high protein breakfast.8 They also had a higher resting metabolism, meaning they were burning more calories even at rest. High protein snacks in another study led to subjects consuming fewer calories at dinner and reporting less afternoon hunger.9

Protein even helps our cells absorb nutrients more effectively. When study subjects ate protein first at a meal, compared to bread first, the levels of glucose in the blood were 40% lower.10 Protein improved how the cells responded to insulin, the hormone that drives glucose into the cells for energy. When people are less sensitive to insulin, such as in Type 2 diabetes, the glucose stays in the blood vessels longer. If it stays elevated long enough, it can stick to proteins and cause damage. Conversely, when people eat protein first, the cells were more sensitive to insulin and cleared glucose out of the blood vessels more quickly.11,12

Higher protein intake has also been associated with a better mood. In an observational study, a 10% increase in calories from protein decreased the likelihood of depression.13 Another study in adolescent elite athletes also showed higher protein tied to better moods.14 The researchers believe that protein supported the production of neurotransmitters, the chemicals used by your brain to communicate. Higher levels of certain neurotransmitters are related to higher levels of happiness. They are also used in the feedback mechanisms that regulate appetite and body weight.15

The standard calculation for protein needs is 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram body weight (0.8 g/kg). However, this amount was determined by balance studies as the minimum level needed before the body begins to break itself down. Studies suggest that 1.5-2 times this amount may be more beneficial for metabolic health, appetite support, and muscle maintenance.16

To calculate your protein needs, take your weight in pounds and divide by 2.2 to get kilograms. Then multiply this by 1.2 grams (or 1.6 grams if you are at your ideal body weight). See my Protein Calculator to calculate your minimum and optimal protein requirements. For a 165 pound person, protein needs would be 90-120 grams each day, which translates to roughly four four-ounce servings. That’s a lot! It won’t happen by accident.

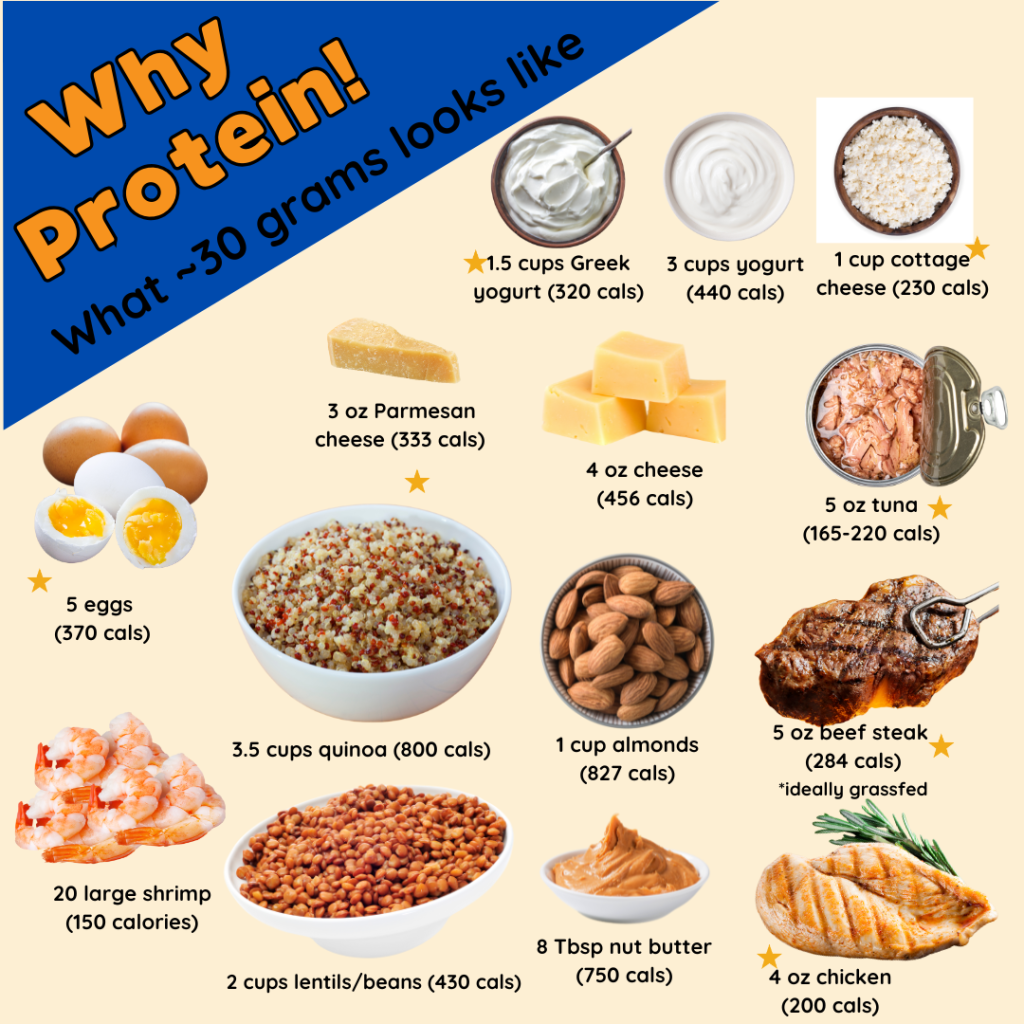

Here are the amounts of some popular protein-rich foods:

| Protein source | Serving size | Protein |

| Beef, chicken, turkey, pork, lamb, fish | 4 oz (size of palm) | 28 grams |

| Seafood | 4 oz | 24 grams |

| Tofu | 4 oz | 12 grams |

| Egg | 1 large | 6 grams |

| Milk | 1 cup | 8 grams |

| Yogurt | 6 oz | 5 grams |

| Yogurt (Greek), Cottage cheese | 1/2 cup | 12-18 grams |

| Cheese | 1 oz | 7 grams |

| Nuts, Nut butter | 1 oz (1/4 cup), 2 Tbsp | 4-6 grams, 7 grams |

| Edamame fresh, Edamame dry-roasted | 1/2 cup, 1 oz | 8 grams, 13 grams |

| Legumes (beans, lentils) | 1/2 cup | 6-9 grams |

A diet emphasis on animal protein was a big switch for me. I grew up vegetarian and had always struggled with the ethics of eating animals. In my 20’s, I designed the diets for a low-carb study and the investigator tried to convince me it would help with my weight struggles. I resisted then, but have found animal protein was the essential nutrient that helped me to feel full, eat less overall, and even think more clearly. As for my choices, I try to choose sources that have been raised humanely, as this is better for our bodies as well. I eat mostly poultry and eggs, fish, and small amounts of pork, lamb and grass-fed beef.

I continue to watch vegan body-builders on social media who say that a plant-based high-protein diet is possible. The drawback with vegetarian options is that they provide significantly more calories per protein which can be tricky if you are trying to lose weight.

I suspect that getting those high amounts of protein are only possible with protein powders. I am not an expert on protein powders, as most of them contain sweeteners (a trigger for me) and I like eating my calories! I have searched the nutrition charts carefully and put together a chart with the very highest protein foods in each category. I would love to hear suggestions from you on your favorite plant-based proteins!

References

- Minghua Tang, Cheryl Armstrong, Heather Leidy and Wayne Campbell, “Normal vs. high-protein weight loss diets in men: effects on body composition and indices of metabolic syndrome,” Obesity (Silver Spring) 21, no. 3 (March 2013): E204-10, https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20078.

- Loren Cordain, Boyd Eaton, Anthony Sebastien, Neil Mann, Staffan Lindeberg, Bruce Watkins, James O’Keefe, et al, “Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century,” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 81, no. 2 (Feb 2005): 341-354, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn.81.2.341.

- Antonio Lancha, Rudyard Zanella, Stefan Tanabe, Mireille Andriamihaja and Francois Blachier, “Dietary protein supplementation in the elderly for limiting muscle mass loss,” Amino Acids 49, no. 1 (January 2017): 33-47, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-016-2355-4.

- Christos Katsanos, Hisamine Kobayashi, Melinda Sheffield-Moore, Asle Aarsland and Robert Wolfe, “A high proportion of leucine is required for optimal stimulation of the rate of muscle protein synthesis by essential amino acids in the elderly,“ American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology and Metabolism 291, no. 2 (August 2006): E381-7, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00488.2005.

- Stijn Soenen, Evaline Martens, Ananda Hochstenback-Waelen, Sofie Lemmens, Margriet Westerterp-Plantenga, “Normal protein intake is required for body weight loss and weight maintenance, and elevated protein intake for additional preservation of resting energy expenditure and fat free mass,” Journal of Nutrition 143, no. 5 (May 2013): 591-6, https://doi/org/10.3945/jn.112.167593.

- Donald Layman, Ellen Evans, Donna Erickson, Jennifer Seyler, Judy Weber, Deborah Bagshaw, Amy Griel, Tricia Psota and Penny Kris-Etherton, “A Moderate-Protein Diet Produces Sustained Weight Loss and Long-Term Changes in Body Composition and Blood Lipids in Obese Adults,” Journal of Nutrition 139, no. 3 (March 2009): 514-521, https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.108.099440.

- Lorenzo Nesti, Allessandro Mengozzi, and Domenico Tricò, “Impact of Nutrient Type and Sequence on Glucose Tolerance: Physiological Insights and Therapeutic Implications,” Frontiers of Endocrinology (Lausanne) 10 (March 2019): 144, https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00144.

- Jamie Baum, Michelle Gray and Ashley Binns, “Breakfasts Higher in Protein Increase Postprandial Energy Expenditure, Increase Fat Oxidation, and Reduce Hunger in Overweight Children from 8 to 12 Years of Age,“ Journal of Nutrition 145, no. 10 (October 2015): 2229-35, https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.115.214551.

- Laura Ortinau, Heather Hoertel, Steve Douglas, and Heather Leidy, “Effects of high-protein vs. high- fat snacks on appetite control, satiety, and eating initiation in healthy women,” Nutrition Journal 13 (September 2014): 97, https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-13-97.

- Alpana Shukla, Morgan Dickison, Natasha Coughlin, Ampadi Karan, Elizabeth Mauer, Wanda Troung, Anthony Casper, et al, “The impact of food order on postprandial glycemic excursions in prediabetes,“ Diabetes Obesity Metabolism 21, no. 2 (February 2019): 377–381, https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.13503.

- Alpana Shukla, Radu Illiescu, Catherine Thomas and Louis Aronne, “Food Order Has a Significant Impact on Postprandial Glucose and Insulin Levels,” Diabetes Care 38, no. 7 (July 2015): e98-9, https://doi.org/10.2337/dc15-0429.

- Ching Lee, Sangeetha Shyam, Zi Lee, Jie Tan, “Food order and glucose excursion in Indian adults with normal and overweight/obese Body Mass Index: A randomised crossover pilot trial,“ Nutrition and Health 27, no. 2 (June 2021): 161-169, https://doi.org/10.1177/0260106020975573.

- Jihoon Oh, Kyongsik Yun, Jeong-Ho Chae and Tae-Suk Kim, “Association Between Macronutrients Intake and Depression in the United States and South Korea,“ Frontiers in Psychiatry 11, no. 207 (March 2020), https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00207.

- Markus Gerber, Sarah Jakowski, Michael Kellmann, Robyn Cody, Basil Gygax, Sebastien Ludyha, Caspar Muller, et al, “Macronutrient intake as a prospective predictor of depressive symptom severity: An exploratory study with adolescent elite athletes,” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 66 (May 2023): 102387, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2023.102387.

- JD Fernstrom, “Dietary effects on brain serotonin synthesis: relationship to appetite regulation,” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 42, no. 5 (November 1985): 1072-1082, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/42.5.1072.

- Angeliki Papadaki, Manolis Linardakis, Maria Plada, Thomas Larsen, Camilla Damsgaard, Maerleen van Baak, Susan Jebb, et al, “Impact of weight loss and maintenance with ad libitum diets varying in protein and glycemic index content on metabolic syndrome,” Nutrition 30, no. 4 (April 2014): 410-7, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2013.09.001.

- Peter Weijs and Robert Wolfe, “Exploration of the protein requirement during weight loss in obese older adults,” Clinical Nutrition 35, no. 2 (April 2016): 394-8, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2015.02.016.